Climate Disaster Resilience and Kolleru Fishing Livelihoods

A Visual Story By

Siva Sankararao Mallavarapu and Bala Raju Nikku

There may be no country in Asia where the impact of climate change cannot be seen and felt. The small-scale fishers in the State of Andhra Pradesh are no exception. Building climateresilient fishing livelihoods is critical now more than ever.

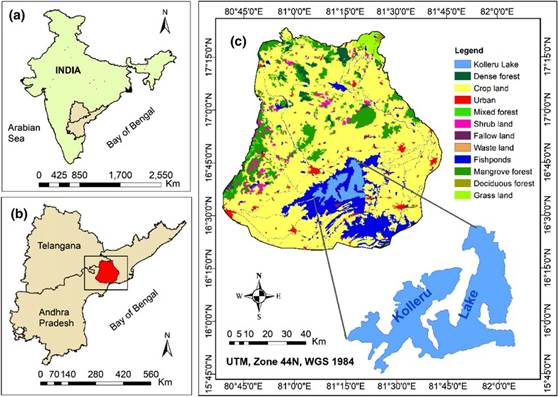

Kolleru Lake, a large freshwater lake in Andhra Pradesh, is under siege. Severe encroachments, shifts from agriculture to aquaculture, salinity ingress, and significant changes in socio-ecological and political conditions are all signs of the profound impact of climate change on this once-thriving ecosystem. The urgency of the situation is pressing and demands immediate attention.

Source Map: Location of Kolleru Lake basin and Land use map (Kolli et al 2021)

Kolleru, recorded as the largest freshwater lake in Asia, is not just a body of water. It’s a unique and irreplaceable ecosystem spread over 30,855 hectares (308 square km). However, the area extends to about 901 square kilometers if the water level reaches the 10th contour (maximum level). According to scientists and wildlife division authorities of the Forest Department, 189 species of local and migratory birds make their nest in the lake and rear the birdlings. Two bird sanctuaries were established despite local people’s resistance, especially the elite owners of the aquaculture ponds; the State bureaucracy (the administrative system of the state), with the help of Supreme court orders, established sanctuaries to protect these bird species, critical to the lake ecosystem and regional eco-tourism. However, depleting water levels in Kolleru Lake in some years created panic among the agrarian and fishermen communities. The drought-like situation and continued encroachments also worry environmentalists and bureaucrats. These challenges put fishing livelihoods at odds with the evolving local and global climates.

Fishing Livelihoods:

Despite their challenges, the fishing communities around Kolleru Lake demonstrate remarkable resilience and determination. This is particularly evident in Mondikodu, a small village habitation near the lake and the Budameru River. Their ability to adapt and continue their livelihoods in adversity is truly inspiring.

Despite being vulnerable to frequent floods, the fishers continue to adapt and survive, illustrating the strength of these communities in the face of environmental challenges.

Visual 1: The local fishing activity, where a man strives to fish in a small flow near Kolleru

Lake, is a testament to the significance of their work in the local ecosystem. It’s a reminder of how these communities are not just surviving, but actively contributing to the preservation of their environment.

The artisanal fishing methods, handed down through generations, are a testament to the rich cultural heritage of the local fishermen in the 21st Century. These traditional methods are not just a means of livelihood but a part of their identity. The image underscores the importance of preserving these traditions and the vulnerability of these fishermen to flooding events that disrupt their way of life.

Story of Yesubabu:

Otukuri Yesubabu, a 48-year-old fisherman from the flood-prone village of Mondikodu near Kolleru Lake, reflects on how the economic and mismanagement of flood disasters and the Kolleru Lake have shaped his life and livelihoods across the last twenty years.

Yesubabu vividly recalls the devastating floods of 1991 and 2024, which destroyed his house and fishing gear and left lasting, frightening memories. The similarities between the two events are striking. Still, he notes the increasing complexity of life for flood victims like him and his fellow fishers around Kolleru Lake over the years.

Visual 2: Mr. Yesu Babu uses this thatched shed to store fishing nets, fodder, boats, and a restroom. It is near his fishing pond on Kolleru Lake in Eluru district, Andhra Pradesh.

This all-in-all shed is a storage area for his fishing gear, such as nets and boats, and a resting place. The image illustrates the simplicity of the infrastructure in the region, underlining the hardships local fishermen face when floods destroy their resources. The semi-structured nature of the shed also highlights the lack of durable housing and facilities in the area.

In 1991, when Yesubabu was a young man, his village faced similar flood devastation due to severe flood flows in Budameru, which is a small rivulet originating in the Khammam district of Telangana, flowing through the NTR district in Andhra Pradesh before draining into Kolleru Lake in Eluru district. Kolleru Lake, in turn, empties into the Bay of Bengal through Upputeru River, the lake’s sole outlet channel.

Yesubabu remembers how local authorities stepped in to help distribute necessities like lemon rice (Pulihora in Telugu), water packets, and other essential supplies to keep the affected families going. Though the relief efforts were minimal, he recalls a sense of community and cooperation, even if the logistics were challenging. He recalls that back then, transportation was difficult. The roads were completely submerged, and we had no way to get out except by boat, reflecting on the difficulties of reaching out to the nearby safe places in the State during that time. But somehow, we managed. The government sent boats to help us move to safer grounds.

Visual 3: Yesu Babu clearing the weeds and collecting food for his fishpond.

This figure shows Yesubabu preparing fodder for the fish in his pond, which is part of his daily routine as a fisherman. He highlights the increased work and reduced fish catch due to infestation and pollution in the Kolleru Lake system affecting his fishpond. The image reflects local fishermen’s sustainable practices, emphasizing their dependence on the lake and natural resources for survival. It also shows how unprepared and expected floods disrupt this fragile balance by destroying fishing infrastructure and impacting fish populations and livelihoods, underscoring the situation’s urgency.

Flood Disaster Management in the past and present:

Comparing the 1991 floods to the Budameru floods of 2024, Yesubabu observes some stark differences further. Although local authorities in 1991 provided immediate relief, the recent floods have exposed more profound vulnerabilities in the region. This time, while some fallow land was used as makeshift rehabilitation centers, these were insufficient to accommodate many displaced families. Back then, it was hard, but at least there was some sense of order in the chaos, Yesubabu says. With more people and fewer resources, the struggle has only worsened in the present times.

One of the biggest challenges for the villagers after the 2024 floods has been the destruction of roads leading to Mondikodu. The floods have damaged critical infrastructure, and reaching the main road or nearby towns has become nearly impossible with no proper road connectivity. This has severely impacted access to essential services, particularly healthcare. In the flood’s immediate aftermath, villagers faced a dire shortage of medicines, and traveling to hospitals for treatment was grueling.

In 1991, it was already hard to get medical help, but now it’s even worse, Yesubabu recounts. The roads are so severely damaged that we can’t reach hospitals easily, and the village has no doctors or medical supplies. He recalls how, in the past, they would use boats to transport the sick or injured to nearby towns, but with the recent floods, even that option has become difficult due to the damaged waterways and lack of boats.

The situation has left Yesubabu and others in the village feeling abandoned by bureaucratic disaster management and local politicians. Despite the government’s promises of aid, the villagers struggle with the same issues they faced decades ago-only this time, the scale of the disaster is more prominent, and the response has been slower. With no proper connectivity to the main road and critical infrastructure in ruins, daily life in Mondikodu has reached a standstill.

For Yesubabu, the recurring floods have become a cycle of loss, rebuilding, and waiting for the next disaster. In 1991, it was hard, but we recovered slowly. Now, it feels like we’re stuck. The floods come, and everything is washed away, but we’re not getting the help we need to rebuild… we need proper roads, hospitals, and schools, but all we get are temporary shelters and food packets, Yesubabu argues.

The 2024 heavy floodwaters submerged many villages in this area when the water level in

Kolleru rose to a critical 12 feet. As the waters rose, access to the neighboring villages Penumalanka, Ingilipakalanka, and Nandigama Lanka in the Mandavalli mandal was cut off, and fishing families lost many days of work and ended up lending money at higher interest rates, pushing them into a debt trap.

The Budameru floods of 2024, much like those in 1991, have once again revealed the fragility of rural communities like Mondikodu village. As Yesubabu looks back on decades of struggle, he can’t help but feel that not enough has changed. The need for comprehensive disaster management, better infrastructure, and long-term support is more urgent than ever, especially in regions that face recurring natural disasters.

“We survived then, and we’ll survive now,” Yesubabu says, his resilience evident. But we need more than just food and water. We need proper roads, access to healthcare, and a plan to prevent this from happening again.” His story reminds us that while immediate relief is critical, long-term solutions are essential to breaking the cycle of vulnerability that plagues communities like Mondikodu.

Intergenerational Livelihoods:

A deepening crisis of demographic shifts threatens common property fisheries worldwide.

Due to the ongoing challenges and lack of hope for the future, many fishers from Andhra Pradesh do not want their children and grandchildren to be involved in fishing. However, it is their traditional and caste occupation (kula vrutti).

Yesbabu also expressed similar feelings but saw pride in transferring his fishing knowledge and skills to his grandson despite his lifetime’s socio-political, economic, and ecological shifts.

Visual 4: Yesubabu’s grandson supports and assists him with fishing.

This visual depicts intergenerational involvement in fishing. It shows Yesubabu’s grandson, Ramu, learning the fishing skills and helping with the work. It illustrates the tradition of passing down fishing knowledge from one generation to the next and emphasizes the role of family in sustaining a fish-based livelihood. The visual portrays how the younger generation participates in the fishing occupation passed on to him against his and his grandfather’s wishes and hopes.

Studying ninth grade, Ramu reflects that learning fishing skills is a good idea. He does not see his future beyond the village, as there are no jobs in the state or the country. Unemployment is everywhere, and young people are taking up odd jobs despite having higher degrees. Ramu is aware of his family’s situation and opportunities and how his family is affected by environmental disasters, such as floods, pollution, and encroachment in Kolleru Lake. This story reveals that community adaptive capacity can come at the expense of socialecological common property systems like Kolleru and vice versa. Ramu knows other young people from the neighboring Visakha and Srikakulam districts who migrate to Gujarat to work in the fisheries sector (often in harsh and exploitative conditions). Maybe Ramu will soon be forced to join the push-pull of climate and political crises, leaving his grandfather to fend for himself.

Gender in small-scale fisheries: Story of Narsamma

Fish is among the few food products in rural economies that generate cash and sustain the subsistence living of poor households. It also may spur and stimulate demand because fish is generally bartered or consumed within the household as a good food source.

Visual 5: Narasamm’s Hut

Narasamma lost her husband a few years ago, and her children left her in search of their livelihoods. Thanks to the State’s NTR Bharosa Pension Scheme of 2024, which includes monthly cash allowances to widows as a form of social protection (Ms.No.43 Dated 13. June 2024). Narasamma receives INR4000 (USD50) per month to sustain her necessities. In addition, she works as an agricultural laborer, which was not used when her husband was actively involved in fishing. She used to sell the fish catch in the village and earn cash to buy household consumables. She remembers that was her best of life, dignity, and worth.

Visual 6: Women’s traditional method of fishing

This brief Narasamma’s life story highlights how a woman continues to engage in traditional fishing in the absence (demise) of male counterparts in the family. It emphasizes the gendered roles of women in fisheries and the significance of conventional techniques that have been used for generations.

The stories of Ramu, Yesubabu, and Narasamma, small-scale fishers of Kolleru, symbolize the livelihoods of fishers who are integral to the Kolleru lake system and underscore the need for improved lake management disaster management policies to protect the fishers and their cultural heritage, and livelihoods.

Acknowledgements:

This photo essay is the first in the Stories of Resilience of Small-Scale Fishers in Andhra Pradesh series. This initiative is part of the Disaster Resilient Futures research project funded through the New Frontiers Research Fund Research (NFRF), led by Dr. Bala Nikku, Associate Professor at Thompson Rivers University. Dr. Nikku is a Co-investigator of the V2V global partnership. Email: Bala Nikku bnikku@tru.ca

Siva Sankararao Mallavarapu and Dr. Srinivasu Kodi lead the Coastal Resilient Futures India Network. Email: Siva Sankararao ssankararao@gmail.com and Srinivasu Kodi anthrosrinu.kodi@gmail.com.